Ghost light: Tim Quirke paints at the edge of the old and the new

In a town where wars once raged and routers now blink, artist Tim Quirke and his subjects live between story and signal.

Time holds strangely in a town like Philippolis: it hangs in the wide sky and the cracked facades of old houses, in sandstone churches and stitched family names, and in the long shadow of vanished wars.

The present can be found behind closed doors: LED lights powered by solar panels, routers humming in darkened hallways, voices carried over WhatsApp calls to children now living in cities or across oceans. The old and the new hold hands here, uncomfortably, but inevitably.

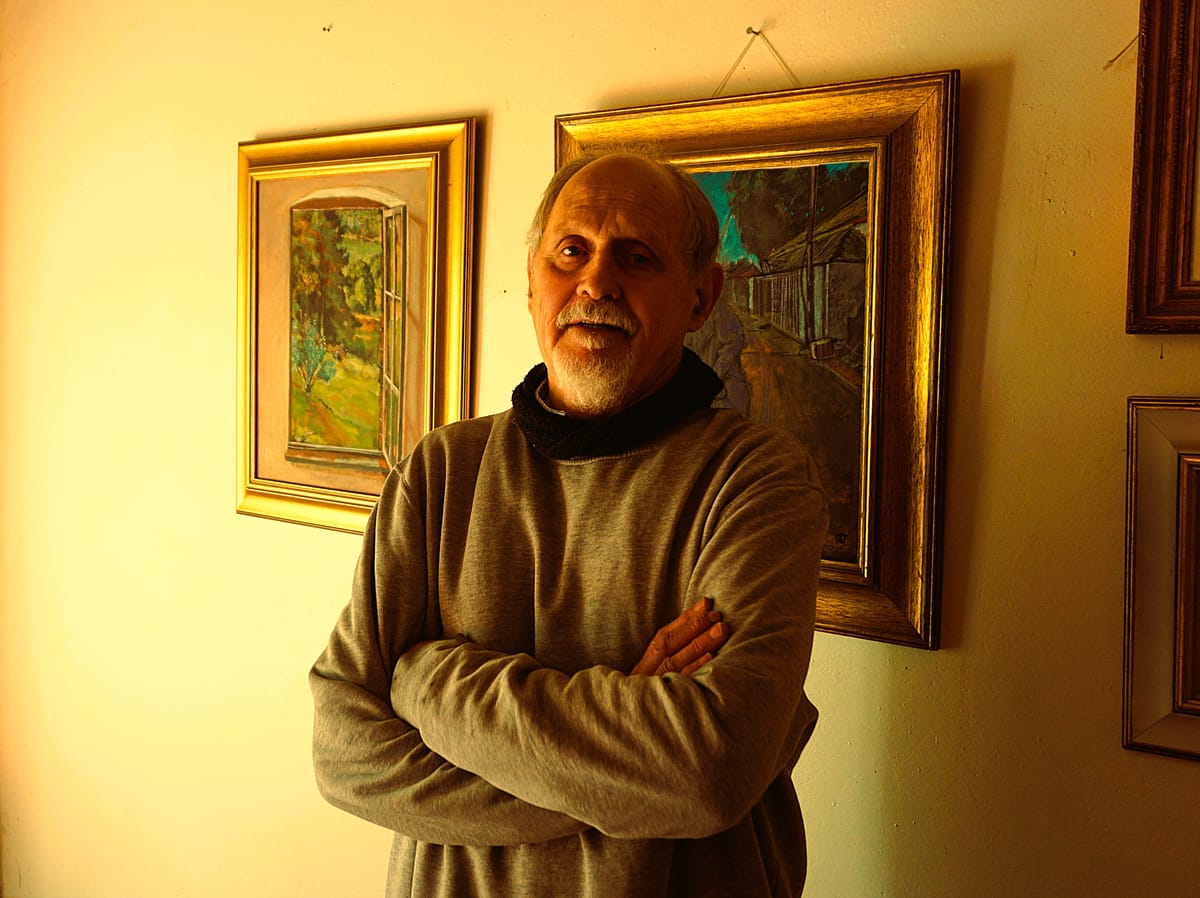

Karoo Times recently spoke with artist Tim Quirke to reflect on his work and the shifting rhythms of life in Philippolis. For Quirke, who moved to this small Karoo town a few years ago from Johannesburg, that uneasy joining has become a central focus.

A formally trained fine artist, Quirke’s work has always engaged with form and feeling, but lately, he finds himself drawn to the tension between two very different artistic traditions: the ephemeral light and gesture of impressionism, and the fractured lens of post-modernism.

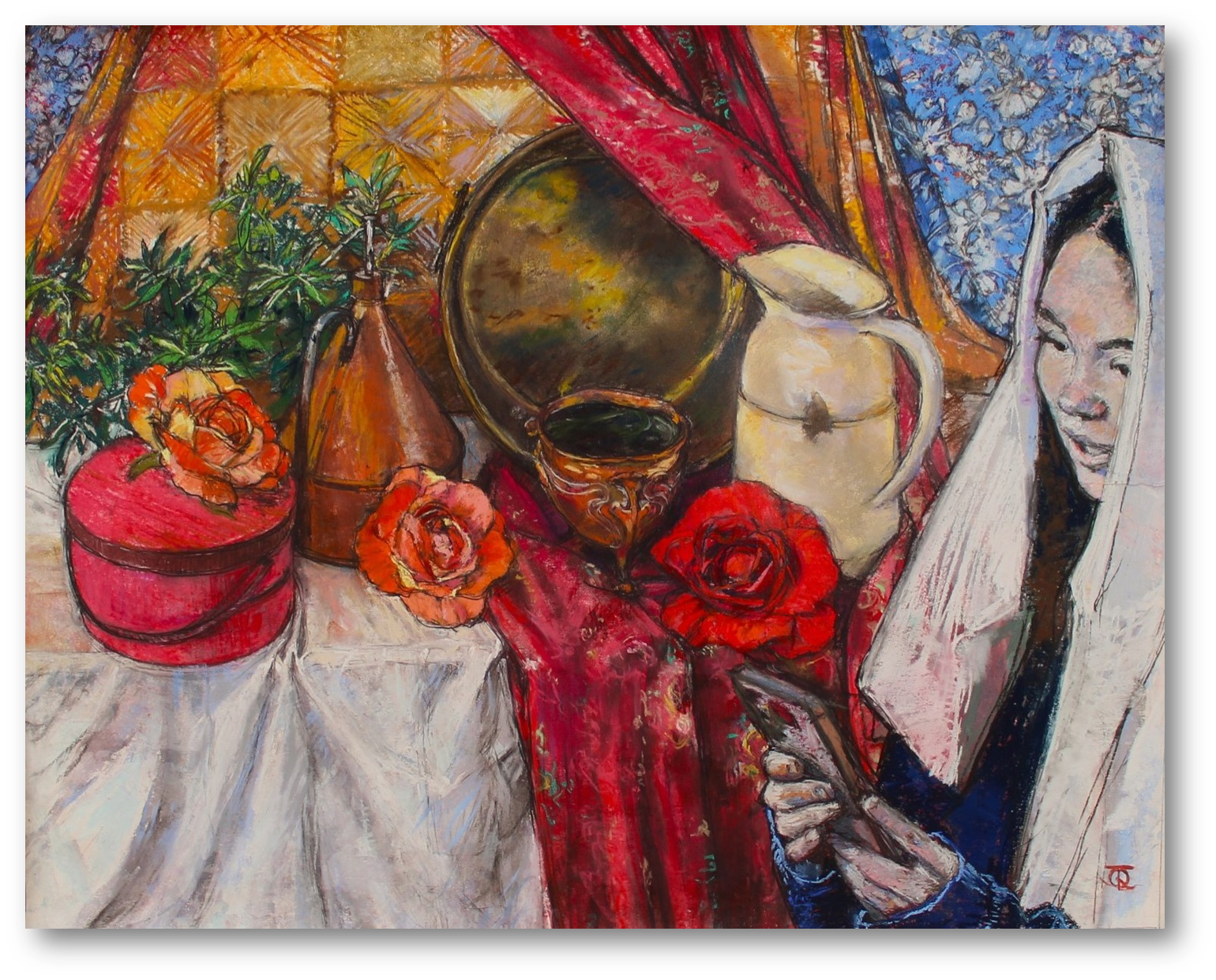

His materials include French pastel, and his subjects are often still lifes made from the objects of this place (enamel jugs, African roadside art) set against symbolic, richly worked backgrounds infused with Jungian archetypes. These are charged images, where the ordinary becomes mythic and the Karoo’s practical surfaces open into psychological depth.

The tension between these modes runs through both his work and the town itself. Outside the local clinic, he sketches people waiting: women, children, old men. Their forms are loose, gestural, drawn in motion and memory.

"I am dreaming of an art of empathy," he said, "where even socialised impulses can be cheated or transcended. I would like to make images of people who are 'seen'."

In another series, ghost figures from the Anglo-Boer War drift silently down modern streets, translucent against iron fence railings. These are the impressions of the past echoing in the atmosphere.

That duality defines life in Philippolis. Farmers still speak of plantings the old way, but their pivots are digitally timed. One man checks his borehole via an app while a donkey cart rattles past his gate. The same building that housed the British garrison during the Anglo-Boer War now has Wi-Fi. The physical world is old but the signals are new.

In such a place, the question isn’t whether tradition and technology can coexist - they already do. The real question is how to live meaningfully inside that contradiction.

Quirke’s work doesn’t try to resolve it. Instead, it dwells in the space between to create layered figures emerging from memory, filtered through the discipline of classical training but informed by the looseness of light and digital afterimage.

As a result, his portraits echo the landscape in their restraint but gesture toward something unsettled beneath the surface.

Quirke spoke plainly of the town’s challenges. “The environment is sparse, except for a surfeit of extreme conditions - heat, cold, poverty,” he said. Yet it’s this very rawness that refines his process. The studio has merged into his home. The work develops slowly - sketches first, then larger forms. He spoke of “refining” and “veracity,” not as technical goals, but as a kind of emotional accuracy.

He also teaches a few local students, some with no prior training, others curious. “I appreciate that it is a step into the unknown for many people,” he said. “Still,” he added, “some have shown real resilience and courage.”

His approach is careful: objects first, then light, then, only when ready, the human figure.

Now, he prepares for his second exhibition in the region, to be held at Waterkloof Brewery. It will feature recent works drawn from the town’s strange, unsettling complexity - a town where wars once raged and routers now blink, where both artist and subject live between story and signal.

Philippolis is a town of coexistence. The NG Kerk and the local internet tower. The farmer with old planting calendars and agri-tech solutions. The schoolchild whose family has lived here for generations, doing online classes during load shedding. Quirke’s work responds to this by refusing to resolve it.

To live and paint in such a place is to stand at the seam where old light meets new image. Here, the enamel jug becomes a totem and the act of waiting is itself a gesture.

For enquiries about his classes, art, or to request a commission, send Tim Quirke a WhatsApp.

Comments ()